|

|

|

- Welcome to Trad Gang.

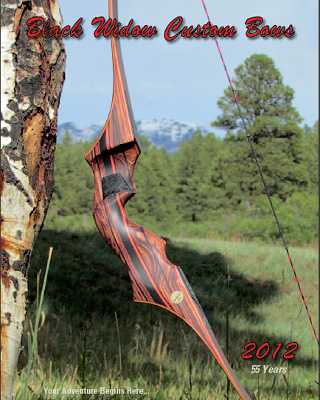

Symetry vs asymetry

Started by Steve Kendrot, September 03, 2008, 10:29:00 PM

Previous topic - Next topic0 Members and 4 Guests are viewing this topic.

User actions

Copyright 2003 thru 2025 ~ Trad Gang.com © |