BOW WOODS AND BOWSTAVES

TOPICS

| Making Lemonwood Longbows |

| Horn and Fibre Tipped Bows |

| Backed and Laminated Bows | | How Backings are Applied |

| Demountable Bows | | Flat-Limbed Lemonwood Bows |

| Making Yew and Osage Orange Longbows | | Flat Osage Orange Bows |

| Reflexed Bows | | Hunting Bows |

LEMONWOOD (Calycophyllum candidissimum), the degame of the wood importers, is a native of Cuba. It is hard, heavy, tough and springy. It comes in small logs or spars and is straight enough to be sawn into bowstaves. It is the most satisfactory and reasonably priced wood of which to make a bow. It grows in the mountains, and most of it is carted by oxen to a port for shipment by steamer. The bark is a reddish brown, rather stringy and somewhat resembles red cedar bark. It has nothing to do with lemons; the name refers to its color. It varies from a light yellow to a light brown and is often mottled. We have found that the spars yielding the very best bowstaves have a distinct apple green streak just under the bark. Lemonwood is a true bow wood, and for an all-around bow, as good as any that comes. The fact that the highest score ever made in tournament for the American Round was made with a lemonwood bow speaks well for its qualities.

OSAGE ORANGE (Maclura or Toylon) belongs to the mulberry family (Moraceae), and is one of our finest native bow woods. It seems to grow throughout the whole of the United States, and is known in many sections as the Mock Orange. Years ago this tree was planted extensively for hedges. The best of it comes from our Middle West. It is a very hard wood, ranging in color from a very pale yellow to chocolate brown. Sometimes it comes in a light yellow prettily mottled with dark brown spots. Since the wood takes an exceptionally fine polish, such a piece results in a bow of unusual beauty.

Osage Orange bowstaves, unlike Lemonwood, come directly from the log section, with the bark, heartwood and sapwood intact. Before the staves are stored away for seasoning, the bark is removed and the staves given a coat of shellac. This permits them to dry out slowly and prevents warping and checking.

Osage Orange bowstaves, unlike Lemonwood, come directly from the log section, with the bark, heartwood and sapwood intact. Before the staves are stored away for seasoning, the bark is removed and the staves given a coat of shellac. This permits them to dry out slowly and prevents warping and checking.

As an all-around bow wood, Osage Orange ranks high. Good staves yield hard shooting, tough, sturdy bows that will stand lots of abuse. This wood possesses none of the temperamental aspects of yew, and for a bow that is equally good in the heat or cold, one good for target work, hunting or roving, Osage Orange is the wood.

Osage Orange Staves may be worked up into Standard Long Bows, the shorter, semi-Indian type flat bows, and the Flat Reflexed Bows. All are good; the maker's personal preference alone being the guide.

YEW (Taxus) is a soft wood. Compared to Lemonwood and Osage Orange, which are hardwoods, it is light in weight. The heartwood of yew is reddish, and ranges in color from light to nut brown. Our American supply comes from Oregon, Washington and California. The yew staves are split or sawn directly from the trunk and come with the bark, sapwood and heartwood intact. After the staves season, the bark, which is quite thin, readily chips off.

During the past couple of years advocates of various inethods of seasoning have pushed their pet claims -some are for kiln drying, some want to place the staves in running water or streams until the sap and resin is washed out. These methods may have merit, but why go to all that fuss when you can pile it up in a nice dry attic and leave it alone for a year or two. Turn it over once or twice for luck if you wish.

Generally, the ner or more grain lines to the inch, the better the wood is. Yet I have seen a yew bow with six grain lines to the inch that shot better and harder than any close grained stock. After making a thousand yew bows in my shop, the writer is of the opinion that the excellence of each bow depends on the individual stave and the care with which it has been handled by the bowyer.

Yew may lose weight and cast in hot weather, it picks up in cold; in freezing weather it may break in your hand, it develops crisals (a peculiar crack that works at right angles to the grain of the wood) which occurs with Osage or Lemonwood only in rare instances, and may prove cussed beyond belief in more ways than one. Yet we are frank to confess that a fine yew bow is a joy to shoot and something to cherish.

Perfect six foot staves of Yew are rare. Most staves will have small pins, the grain is sure to dip at some spot and little knots may appear. Since it is easier to secure this wood in lengths of 3'6", two such pieces are joined to make one six foot piece.

OTHER WOODS

Ash, hickory, black walnut, sassafras, ironwood, mulberry, apple and many other native woods have been made into bows. These woods are not true bow woods, but have been used only because nothing better was at hand. They produce bows that shoot fairly well in the beginning, but they soon lose cast and become flabby and weak. When they dry out thoroughly they become brittle and break.

This is true of the average run of these woods, but sometimes a bow of northern ash or hickory yields a fair weapon. There is a tree called hop hornbeam, with a white, very tough wood resembling hickory. This makes a fair bow.

MAKING LEMONWOOD LONG BOWS

Nine-tenths of all good bows made in this country are Lemonwood. Lemonwood bowstaves are different from yew and osage staves. They are sawn from the spar. The trees grow straight and round and the grain runs true, making it possible to saw out staves with the grain running from end to end. While it may be better to make a Lemonwood bow with the grain running flat, in practice it doesn't seem to make any difference whether the grain runs flat, diagonally or some other way. This is such a hard, dense, close grained wood, that the direction may be ignored.

In my shop Lemonwood Bowstaves are prepared in various ways. There are plain square staves, square staves backed with rawhide or fibre, roughed out or semi-finished plain staves, and roughed out or semi-finished staves backed with rawhide or fibre.

Staves are also selected for quality, as you will see in the catalog. The Blue Ribbon Staves are the cream of the crop.

From these staves self and backed bows may be made. Your bow may be plain ended, that is, have the notches cut into the wood itself, or you may tip it with cow horn, stag horn or fibre.

Semi-finished bowstaves have a good portion of the preliminary work done. Their general outline is that of the finished product. Square staves must first be planed to the approximate shape of the bow. If you are going to make a plain self bow, the first work is done on the back. Staves from us have the backs marked. No work need be done on the back of a rawhide or fibre backed stave, since the backing is smooth and ready for sandpapering and polish. A self bow is one that is made of a single piece of wood, without backing.

The tools needed are-two small steel block planes, one set fine and one set very fine, (and they must be sharp), coarse and fine wood rasps, fine wood file, six inch round rat-tailed file, coarse, medium and fine sandpaper, steel wool, jackknife and a scraper. (The Hook Scraper No. 25 made by the Hook Scraper Co. is excellent.)

Making a Plain Self Long Bow, Plain Ended

With a square stave in your possession, smooth the back with the plane set very fine. If the plane digs in, turn the stave around. Plane the back smooth and finish it with the scraper. Around the middle of the stave draw a pencil line. One inch above this line draw ahother. Three inches below the center line draw another. This four inches will be your handle, and it is so placed to permit the arrow to leave the bow one inch above the true center.

Now look down along the stave. While Lemonwood bowstaves are reasonably straight, very few of them are absolutely true. There is bound to be some side warp. Straighten the stave by planing. If the warp is to the right, take off sufficient on that side to straighten it. At the same time you will, of course, be tapering the stave. On most staves a little planing is sufficient; more work is necessary with others. A stave with a concave or reflexed back is sought after. The bow is built against the natural tendency of the stave to warp in this direction, and usually results in a better casting bow. When your bow has been straightened as to side warps, you want a true center line penciled down the back, so that you may lay it out according to the following tables of measurements. Insert a pin or thumb tack in each butt end of the stave, and stretch a string between them. See Plate 2.

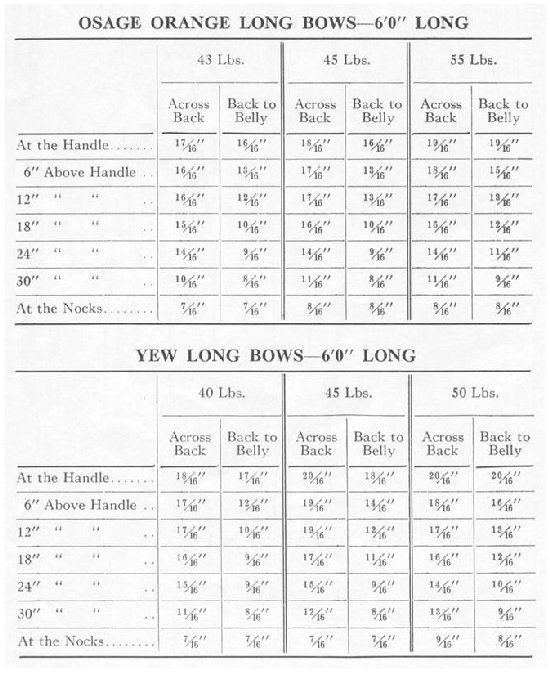

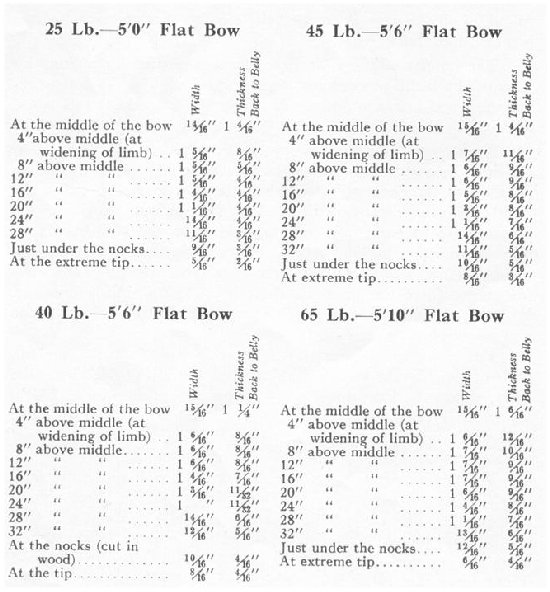

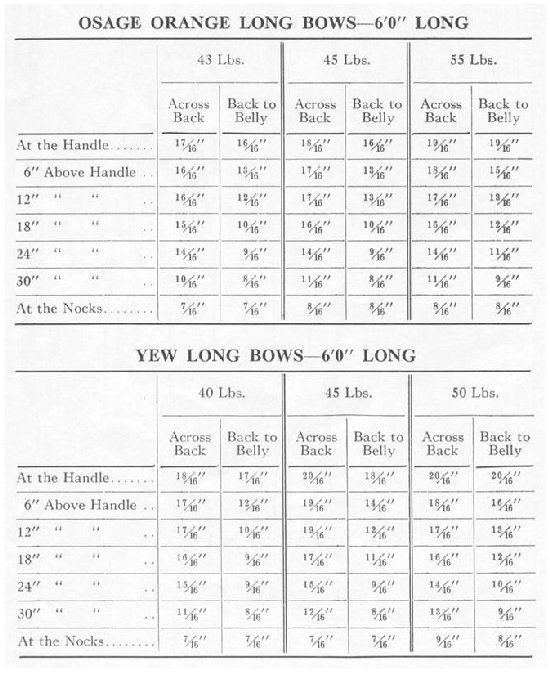

The following tables give actual measurements, in sixteenths of an inch, taken from finished Lemonwood bows 5'0", 5'6" and 6'0" long. The weights (the pull in pounds) are given. Since bow making is a non-dimensional art, these figures are not absolute, and the measurements of a 60 pound bow may result in one of 45 pounds, or some other weight. You can always take off wood, hence it is better to figure on making your bow stronger-four or five pounds more than the finished bow will be.

Now, using your center line, measure off on each side of it half of the figures given under the heading "across back", depending, of course, on whether you are making a 6'0", 5'6" or 5'0" bow. Connect up these measurements and plane down to this line-just up to the line, not past it-this will give you a little leeway. Plate 2.

Then, on the tapered sides, pencil in the belly measurements - that is, the distance from back to belly, or thickness of the bow you propose to make. Plane down on the belly side up to these lines. Round off the handle section until it looks like cross section "A", Plate 2. Continue this rounding of the belly to the ends, so that cross sections look like those on Plate 2.

One of the commonest faults of amateur bow makers is to take off too much wood in the upper limbs and not enough just above and below the handle. The result is that only two or three feet of the entire bow works or bends, undue strain is placed on these weak spots and the bow breaks. A good bow should be stiff at the handle, a distance of about 6", and then the entire limb should bend evenly to the tip. A long graceful curve is to be striven for. See Plate 7. A distinct dip should be made above and below the handle-called the Buchanan dips. The handle or grip proper takes up 4", then the dips begin and the dips take up about 1" on each side of this 4". Look at the finished bow on Plate 2.

If you bought a roughed out stave, practically all the prelitninary work has been done for you, and making the bow is a far simpler job.

It is best to work slowly and cautiously, always remembering that it is a simple matter to take off wood, but impossible to put it back on. When you have one limb about finished, place the tip on the floor and bend the limb. You can tell if it is far too strong or about right. Look at the curve the limb is assuming. There may be spots in your stave that are difficult to plane. The wood rasp may be used on them to advantage. Keep your bow wider than it is thick, or, after you have strung it, it may turn. When you have both limbs worked out, you are ready to cut the notches in the ends of the bow.

Begin an inch down from each end, and with the round file, cut notches diagonally on each side on the ends as shown on Plate 2. Do not cut the notches across the back, because the grain of the back must be left whole and without breaks. The notches should be at least Ys" deep. After you have finished with the notches a preliminary stringing or bracing of your bow is in order. It is assumed that you have made, or now will make, a bowstring as described under string making. Read carefully "Stringing or Bracing the Bow". Slip the loop or eye of the string over the top limb, run it down the bow the proper distance (given under "Making Bow Strings"), fasten the lower end to the bottom notch, and brace the bow. Lay the strung bow on the floor and look at it. If the limbs bend evenly and both alike, you are ready for a trial draw. If they do not bend evenly, it will be necessary to unstring your bow and scrape away wood from the stiff portions. Scraping is safer than planing, as you may easily take off too much.

You should also look down along your strung bow and see if the string bisects the belly. If it does not, but throws off to one side, your bow has a turn in it. This is corrected by taking off wood from the side of the bow opposite, i.e., if your string bears to the left, take off on the right side of the bellv and vice versa. Turning is usually caused by "stacking" a bow, which means it is thicker from back to belly than it is wide. Flat, Semi-Indian Type Bows have no tendency to turn because they are ever so much wider than thick. While it is said a bowstring should bisect the belly of a long bow, in practice a bowstring that throws off to the left-the arrow side of the bow-is no objection, at least, that is the writer's opinion. Many fine osage hunting bows I have used were made with this in view. Then the plane of the arrow nock and the string are about the same, and the arrow goes straighter to the mark

After your bow has been corrected where needed, string or brace it again. The next step is tillering it, which means working on the limbs until they bend evenly and are well balanced at full draw. There are two ways to do this. First, pull your bowstring five or six times a distance of twelve to fifteen inches. This settles the wood a bit. Now have a friend draw the bow about half the arrow length and get off and look at it. You can easily see if it is bending nicely. If it isn't, mark it with a pencil, and take off wood where needed. (Whenever you scrape off a bit of wood, pull your bow a few times to settle the new bend.) Continue this until the bow is at full draw. Lengths of arrows are given under "The Arrow" in the "Fundamentals of Archery". When, at full draw, the bow bends evenly and the limbs have a graceful arch, you are ready for a final very light scraping, coarse and fine sandpapering and finishing.

The second method of tillering is to make yourself a tiller. This is a wooden instrument with a notch at the top to hold the handle of your bow and other notches cut in the side to which you can pull the bowstring. See Plate 7. Space the notches for the string three or four inches apart until the last one is the proper draw length from the handle. Now, by stringing your bow and drawing it to the top notch you can get off and look at the bend. Pull it up notch by notch until the full draw is accomplished and you can see your bow at full arc.

The finish on your bow is a matter of taste. The smoother you sandpaper and steel wool the wood, the finer will be the polish. A good one is orange shellac and a bit of linseed oil. Dip a soft rag in a drop or two of the oil, then dip in the shellac and rub it on the bow. Dip and rub, dip and rub, until the whole has a fine polish. A couple of coats of good varnish, steel wool rubbed between coats, is good too.

The finish on your bow is a matter of taste. The smoother you sandpaper and steel wool the wood, the finer will be the polish. A good one is orange shellac and a bit of linseed oil. Dip a soft rag in a drop or two of the oil, then dip in the shellac and rub it on the bow. Dip and rub, dip and rub, until the whole has a fine polish. A couple of coats of good varnish, steel wool rubbed between coats, is good too.

An attractive handle on a bow dresses up the whole weapon. Colored cords, braids or tapes may be used. Fancy dyed leather with a narrow binding of a contrasting hue is fine. A grip of heavy calfskin, laced up the back with a thin leather thong looks sturdy and businesslike.

You laid out the handle when you started the bow. For guides draw these pencil lines in again. The back of the handle is padded so that the grip is thick and comfortable. A block of soft wood, 4" long and as wide as the back of the bow and half an inch thick is glued or tacked to the back of the handle. Then it is tapered off and rounded so the grip feels right. Your handle material goes on over this wooden pad and belly of the bow. Glue it on with waterproof glue and wrap it tight.

A string keeper adds the last neat touch. Drill a very small hole in the upper extremity of your bow, run a leather thong or fancy cord through it and tic it to the top of the eye in your bowstring. Pull it up so the string lays along the belly of the bow. This string keeper prevents the string from sliding down the bow limb.

HORN AND FIBRE TIPPED BOWS

Horn or fibre tipped bows are made exactly the same as plain ended bows. The only difference is in the tips. The traditional shape of horn tips is shown on Plate 2 - "Cow Horn Tips". The top has a scroll and the bottom is pointed. Stag horn tips are pointed while fibre and aluminum tips are shaped as shown on the same plate. Cow or Steer Horn and Stag Horn Tips have tapered holes, and the ends of your bow must be tapered to fit them. With the wood rasp and file, taper the ends of your bow, so that they fit 3/ perfectly inside the horns. Five foot bows take a horn with a 8" hole, 5'3" and 5'6" takes 7/16" holes and 6'0" bows take horns with 1/2" holes. The holes in fibre and metal tips are usually 3/8" and are bored straight. The illustrations on Plate 2 depict this and show how the ends of the bow should be worked to fit these various tips. It is well to both glue and pin the tips to the bow. A very small hole to take an 18 gauge brad is large enough, and the brad should go right through and be filed off even with the sides of the tip.

BACKED AND LAMINATED BOWS

A backed bow is any bow-flat or long type-that has been backed with a substance intended to prolong its life or improve its shooting qualities. The bow consists of two pieces; the bow itself and the back. A laminated bow is a bow made of three or more pieces, joined or laminated together. Wood, rawhide, fibre, fibre glass, sinew and various plastics are used for backs and for laminated bows.

A wood backing is a piece of fine, straight grained, tough white hickory, ash, elm or lemonwood. It is one-eighth to a quarter of an inch thick and adds strength and cast to the bow. If the wood back is put on so that the stave has a reflex toward the back (in other words, the back is concave) this adds to the cast. Before the new resin and plastic glues were developed, backing a bow with wood was a chancy business and there were many failures because of the back and belly of the bow parting company. Now, with these new glues, joints are actually stronger than the rest of the stave. The secret of making good joints is to be sure the back and stave are absolutely flat so that contact between the two pieces is made everywhere.

The rawhide for backing bows is drum head rawhide, a clear parchment-like calfskin. This is exceedingly tough and strong and makes an excellent backing. The black or red fibre used in bowmaking is quite thin and makes a very pretty back. The fibre polishes very well and the colors are attractive. Neither rawhide nor fibre increase the strength of a bow much. Their principal function is to protect the back of the bow from hard knocks and to keep splinters from lifting.

Sinew is what the Indians used to back their bows, but it is difficult to get, unless you have access to the dead animal itself. The longer the strands of sinew the better, and the longest comes from under the back bone. The hock tendons are good too, but are much shorter.

Fibre glass backings are made of spun glass fibres laid in a plastic to hold them in place and thus make a workable product. Plastics have been developed that are hard and horn like and make fair backs and facings for laminated bows.

HOW BACKINGS ARE APPLIED

Wood-See that the back of your stave is absolutely flat. Sand it well with coarse sandpaper. See that your backinp, piece is absolutely flat also, and well sanded with coarse abrasive too. Apply glue (Casein, Weldwood or any resin glue) liberally to both backing and bow back. Cut a pressure board of pine or other wood Y4" thick and Y4" narrower than your wood back. Place this over the back and bind your pressure board, wood back and bowstave together with rubber strips cut from an inner tube. Cut the strips Y2" wide and use plenty. See that glue squeezes out all along the joint. Let it dry for at least a day before working on your backed stave.

Rawhide-Scrape or plane the back of your stave smooth and sandpaper it with coarse sandpaper. Clarified calfskin or rawhide comes in various widths. Two pieces are used on a bow. Each length covers half the back. Soak the two strips in cold water for ten minutes and wipe off the excess moisture. The strips will now be soft and pliable. When you take the calfskin out of the water stretch it very carefully. It will have a tendency to curl-apply the concave side to the bow back. Apply smooth, thick, creamy waterproof glue along the back of your stave. At the center tack one piece to the back, run the rawhide up to the end, smooth out all air bubbles and tack it at the tip with a thumb tack. Butt your second piece against the first, tack it, and run it down the second half of the back of the stave. Be sure all air bubbles are worked out and the rawhide adheres everywhere. Watch it for half an hour or so and keep working it down where needed.

Fibre-Fibre comes in strips and is glued directly to the back with waterproof glue. It is best to cut a thin slat (Y4" thick) exactly the width of your bow back, for a pressure board. Lay the fibre in the glue on the back, press the slat on, and bind down with rubber strips Y2" wide cut from an inner tube. Let it dry overnight and remove the slat.

Sinew-Secure three to four dozen Achilles heel tendon sinews. These will run from 6" to 12" long. Shred them fine by pulling apart with flat jawed pliers. Rough the smoothed back of your bowstave with very coarse sandpaper. Apply Special Formula Glue (a glue developed by the writer for glueing sinew to sinew, sinew to wood, horn to horn and horn to wood) liberally along half the back. Take a handful of shredded sinew, work it in lukewarm water for a few minutes, squeeze out all water, and pull out a soft strand. Lay it lengthwise in the glue, and continue this process until you have covered the back with the strands of sinew. Lap them, and so arrange them that the back is covered. Then do the same to the other limb. Apply another layer and continue this process until you have 1/8" to Y4" of sinew and glue on the back. Apply glue between each layer. Let it dry for at least two weeks, and you will have a hard, hornlike back. The longer this back dries, the harder it gets and the more cast it develops.

Fibre Glass-Fibre Glass comes in the form of strips ly2 wide by 1/16" to 3/32" thick and about 5'6" long. It isglued to the flat back with a resin glue. Some fibre glass backs come already glued to a very thin strip of wood, and the thin wood piece (plus fibre glass) is glued to the bow back. A pressure board should be used-as described under Wood Backs. To get a good glue joint with fibre glass is quite a job.

To improve the cast of the finished bow, backs are glued to the stave while it is held in a reflexed position. Make a wooden form 2" thick, 2" longer than the stave you are working with and 6" wide. One edge of this wooden form piece is worked into an arc, the cord of which is 3" to 4". By bending around this form, your stave will come out with a concave back. The backing goes on the form first, stave on top. Start at the center, and with rubber strips (spaced I" apart) cut from an inner tube, tightly bind down one limb. Bind all around the form. Then bind down the other limb. Before binding to the form, the stave should be tapered on the flat belly side. Begin 20" down from the ends and taper to 3/8" at the ends. This will make bending around the form a lot easier.

DEMOUNTABLE BOWS

A demountable bow, or carriage bow, is a bow that is made to come apart. The two limbs are joined under the handle in a stee! tube, which acts as a ferrule, so that the top limb may be pulled out. The advantage of a bow of this kind is its convenience in packing and carrying. A 6'0" bow reduces itself to a package a little over three feet long.

The handle consists of three pieces of seamless steel tubing - one piece 4" long and two smaller pieces 2" long. The two shorter pieces are fitted to the ends of your limbs; and care must be taken to see that the billets of lemonwood, yew or osage, whichever wood you are using, fit snugly and perfectly into these 2" pieces. A hole 3/32" in diameter is drilled through steel and wood and a long thin nail driven through and filed off even with the tubing. This is to hold the tubing securely in place. Then the two limbs with their steel ends are inserted into the longer tube and lined up; another long nail is pinned right through the large 4" tube and the lower section, which is held permanently in place. A socket and post is made from a nail 3/32" in diameter for the top limb so that it lines up easily each time you assemble the bow. See Plate 4.

It is essential that when the two 2" pieces of tubing are fitted to the bow ends that you do not cut shoulders of any kind. The wood of the limbs must fit inside the tubes, so that there is no chance of a break starting at a shoulder.

FLAT-LIMBED LEMONWOOD BOW

The Flat, Semi-Indian type bow merits special consideration. Although the idea is not new, its present growing popularity is due to the many advantages it possesses. The fundamental principle of this type of bow is that a wide, thin, flat slat will bend easier and be less liable to fracture than a square stick of the same volume of wood. This feature makes it possible to use a 28" arrow in a 5'6" bow, and, naturally, since a shorter bow of the same weight will shoot farther and faster than a longer bow, you get a flatter trajectory. Further, a well proportioned flat bow is easy to string, sweet to use and has lots of punch. It is well established that the nearer to the center of a bow the arrow can pass, the less side variation there is in its flight-hence the narrowed handle of the flat bow, thickened from back to belly for the necessary stiffness and strength. See Plate 3.

MAKING THE FLAT LEMONWOOD BOW

The Flat Bow is the easiest of all bows to make, and is, therefore, an excellent type for the beginner to attempt. It presents fewer problems than the making of a long bow, yet the finished bow is entirely satisfactory and a worthwhile weapon in every respect.

The Flat Side of the stave is the Back. The side with the handle riser is the Belly. Caution: Do not attempt to bend your stave until you have tapered the limbs on the sides and belly, as described below, otherwise the riser may pop off. If it should loosen, take it off, smooth off the surface of the riser and stave, glue it back into place with casein glue. Use rubber strips cut from an old inner tube to hold it in place while the glue is drying.

Since a 5'6" Flat Bow is the proper length for the greatest number of archers, let us begin with that size stave. The Flat Bowstave you get from us will look like that shown on Plate 3.

It will be 5'6" long, IY2" wide and 9/8" thick in the limbs. The handle riser or thickening piece will be glued in place and be sawn to the approximate shape of the finished handle. At this point it will be I Y2" thick, ample bulk to result in a stiff middle.

The back of the bow is left flat. Smooth it up with a sharp hand plane set very fine. At each end of the stave, measuring from side to side, place a dot. These marks will be Y4" from the edges. Measure off Y4" from each side of the center mark and make two more dots. Eighteen inches from each end of the stave draw a line across the back. Connect the ends of this line with the two dots which are Y4" from the center point. Plane off the wood on either side of these lines. This gives the limb taper. See Plate 3.

Note: Sometimes your stave will not be absolutely straight, but may have a side warp. In this event the above measurements would not hold, because it would then be necessary to take off more wood on the side toward which warp curves, i.e., the concave side. When you finish tapering the limbs, however, each should be a long, narrow, triangular figure measuring ly2" wide just above the handle riser and continuing this IY2" width for about a foot, then tapering to Y2" wide at the ends of the stave.

The Belly side of the bow is tapered from the handle riser, where it is @/8" thick to Y4" at the ends-just a slight taper. Then round off all the corners on the belly side, so that the cross section is a low, flat arch.

The handle of the Flat Bow is accomplished by making an abrupt, sharp dip in the riser, rounding off the corners and working the wood into the limbs. A coarse file is good for this work. Plate 3.

Next comes the notches for the bowstring. These may be cut into the wood, or be of stag horn, cow horn, or metal. Plate 3 shows how the ends will look when the notches are cut into the wood. A round, rat-tail file 8" long is excellent for this work. If you wish to embellish your bow with cow or stag horn tips, the ends of the stave must be carefully tapered and rounded into a cone that will snugly fit into the horn bow tips. Be very careful not to force the wood into the horns, or a split will result. Work slowly and carefully, and when the horns fit perfectly, glue and pin in place.

Put the loop of your bowstring over what is to be the top limb of the bow in such a fashion that the string lies along the belly. Slide the loop down a few inches below the notch (3y2"), lay it out straight along the bow and fasten at the bottom with a bowyer's knot (timber hitch). After the bow is strung or braced the string should be 5y2" from the top of the handle riser.

When your bow is cut out, and before you apply the final finish, it should bend evenly in both limbs and its shape should be a segment of a circle with a flattened middle of about 6". One of the commonest faults of amateur bow makers is that their bows are stiff for about two feet in the middle. Too much wood is cut from the upper limbs which leaves them too weak. The result is that only about 24" of the whole bow does the work of bending. This sets up undue strain on your weak limbs and breakage occurs. Plate 7.

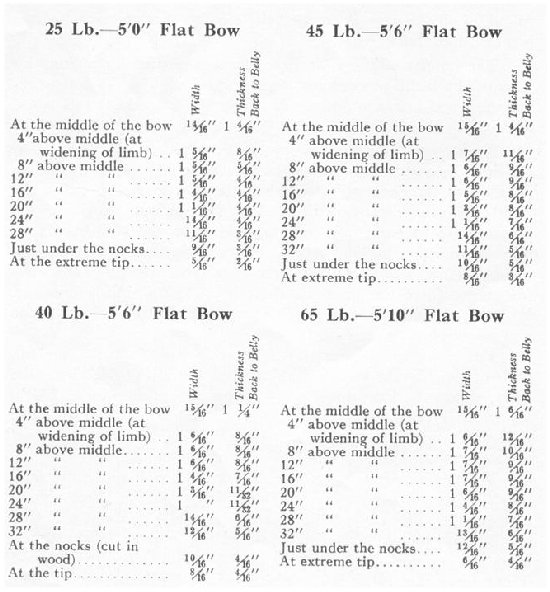

The following measurements are taken from finished flat bows of Lemonwood. The lengths of the bow and weights are given, but since bow-making is non-dimensional, these tables are not absolute. In other words even though you might work closely to these figures, the bow may or may not be the weights given. It is better to leave a bit more wood all around, and then scrape down to the weight you wish.

MAKING YEW AND OSAGE ORANGE LONG BOWS

Yew and Osage Orange bowstaves differ materially from those of Lemonwood. They are cut directly from the log and have the bark, sapwood and heartwood intact when first cut. The bark is usually taken off the osage orange staves to help them season. The bark on yew is thin and after a year's drying can be taken off with a draw knife quite easily.

Both of these woods may be had in full length staves of from 5'0" to 6'0". They also come in billet form. Billets are two pieces cut preferably from the same wide short piece. Since these woods have small knots, pins and other minor defects, it is easier to get two clear pieces 3'6" long than it is to get a single long, sound clear stick.

If you intend to make your bow from billets, they must be joined to give you sufficient length. There are two methods of joining yew and osage billets. The simplest way is to join them in a seamless steel tube lys" in diameter. The ends of the billets are carefully rounded so they fit perfectly in the 4" tube. After they are in place, and the two billets lined up for straightness, two pins of metal are driven through tube and wood and riveted in place. Drill a hole I" from the tube end right through and insert your pins-one in each billet end. Any nail 3 /32" in diameter will do.

The other method of joining is by means of a bowyer's or double fishtail joint. See Plate 4. Square up one extremity of each billet so that you have ends 4y4" long, IY4" from heartwood to sapwood, and ly4" wide, as shown on Plate 4. Paste a piece of paper on the back of the sapwood side of the squared ends on which to pencil the outline of the joint to be made. First measure down 4y4" and draw a line. The joint you are going to cut is a dove-tailing of two ends. One end of your billet will have two points; the other three. The two pointed end goes into the three pointed end. To make the two prongs, divide the end of your billet into three equal parts; make pencil points at these divisions. Draw lines from these two points to the outside of the bottom of your first line across the back, which is 4y4" down the ends of the billets. Place a point in the center of this cross line, and draw two triangles as shown on Plate 4. With a band-saw or hack-saw cut out the center and side pieces as shown. This gives you the two pronged end. The receiving end is three pronged as shown. Divide the tip of the other billet in half, and the cross line in thirds. Draw in your lines as shown and saw out the wood where required. If you make the joint carefully, it should fit perfectly. No light should shine through. If it isn't a perfect fit, you may work it in with a file.

When the joints fit nicely, apply heavy, creamy waterproof glue liberally. Force the joint together and tightly bind the whole joint with rubber strips Y2" wide cut from an inner tube. Leave about a quarter of an inch between the rubber strip wrappings so the air can get at the glue. After the joint is wrapped with rubber strips, line up your stave carefully. See that it is straight. A very slight tilt or reflex towards the back is permissible. You may shift the joint while the glue is wet and the rubber will hold the shift in place. Leave your work tightly wrapped for two days, remove the rubber and let the joint dry for a week.

When the joint is perfectly dry, it is a good idea to round it off to approximate handle shape and bind it tightly with thin linen fish line or linen twine. This is an insurance against accidents which might open up the sides of the double fishtailed joint. After your stave has reached this point you may proceed to make the bow the same as if it were a single stave.

The most important thing to remember in making both yew and osage bows is that the GRAIN MUST BE FOLLOWED. Place your stave in a vise, and with a draw knife take off the bark if it hasn't already been done. With osage, removing the bark is all that is necessary. Scrape the back clean and smooth with a Hook Scraper No. 25. With Yew it is necessary to reduce the white sapwood to 3/16" thick evenly along the back. Do this with a sharp draw knife and be sure to folllow the grain; dip when the grain dips, let it rise where it rises, don't try to flatten the back or you will cut across the grain and your bow will break. Your guide line is the separation point of the red heartwood and wbite sapwood. Next look along the stave from end to end. if it has a side warp or is not straight, take off wood from whichever side needs it.

Measure down 1" from the end of your joint or metal tube. Consider this point the true center of your bow. Measure from this point 3'0" in either direction and cut off any excess material.

The joint or metal tube will now come under your handle and the arrow will leave the bow I" or ly4" above the true center.

Plate 4 gives you various steps in the making of 6'0" Yew and Osage Orange bows, and the following tables of measurements give you actual figures on which you may lay out your stave. Base your back measurements from side to side of a true center line arrived at by means of a string and thumbtacks as described under the section, "Making a Lemonwood Long Bow".

Bear in mind that the figures were taken from finished bows, but that is no guarantee that if you follow them your bow will weigh the same. If you wish a 45 pound bow follow the measurements for the next higher weight given, and then you may scrape your bow down a bit if it results in too strong a bow. You can always take off wood, but you can't put it back on.

Following the grain on the backs of both yew and osage is very important. Be sure you do it, regardless of dips and rises. On the belly of yew bows, it is well to leave a little more wood where there is a pin or small knot. When the bow is finished, these look like small warts about a quarter of an inch in diameter. This is necessary to prevent crisals at these points.

Since you have plenty of depth at the handle, you can make it IY4" from back to belly and cut quite sharp dips just above and below the grip. This makes for softness in shooting. Be sure when your bow is tillered, as described in making Lemonwood Long Bows, you achieve a long graceful arc from the handle to the ends. See Plate 7.

When working on the belly side of your bow, the rough work may be done with a sharp draw knife. Some staves may be finished with a hand plane while others may have to be worked into shape with scraper and wood rasp. With some osage staves it may be necessary to practically fashion the entire belly with coarse and fine rasps.

The actual making, finishing and handling of the bow is similar to those of lemonwood. Naturally, it is impossible to foresee and advise against every possible contingency in bow making and it is expected that the craftsman will have sufficient intelligence to help him over rough spots.

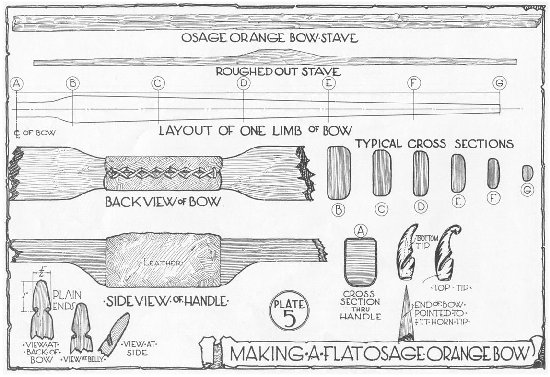

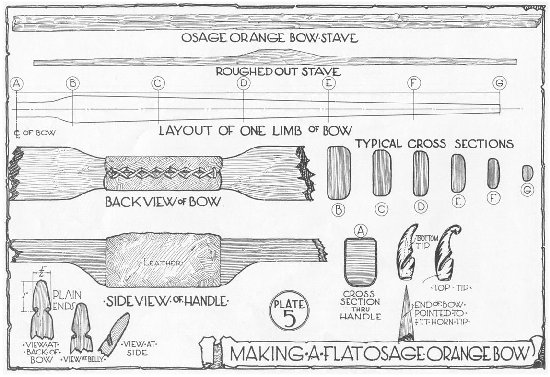

FLAT OSAGE ORANGE BOWS

Osage Orange lends itself beautifully to the Flat, Semi-Indian Type of bow. Read again the section on making the Flat Bow of Lemonwood. With an osage stave 5'6" long in your possession, the first step is to transform it into a Flat Bowstave.

Remove the bark if it has not already been taken off, and clean up the back; be sure to follow the grain when using the draw-knife. Determine the center of your stave. One inch above the true center draw a line around the bow; 3" below the center draw another line around the stave. This is where your handle will come. Refer to Plate 5 and note bow the handle looks. With draw-knife and coarse wood rasp, work your handle to this shape. The abrupt dips at either end of the handle riser flow gracefully into the flat limbs.

At the widest part of your limbs-just a bit below where the handle riser dip disappears into the limbs, your stave should be IY4" to IY2" wide, depending on how wide your original stave was. It should be Y4" through from back to belly, and taper off at the ends 5/16" from belly to back. Next taper your sides. Measure in from each extremity 18", and draw a line across the back. Place a dot at each end. Measure Y4" to either side of this dot. Connect up the ends of the line across the back 18" down, and you will have a triangle with its base the width of the stave and the apex Y2" across. Plane down to this line and lead into the sides so there are no harsh lines. Consult Plates 5 and 7. Round off the belly into a low flat arch, cut your notches, brace your bow and tiller as described. Finish and handle to suit your fancy.

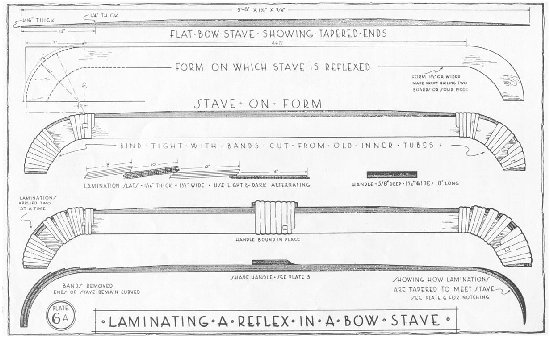

REFLEXED BOWS

Reflexed bows have the ends reflexed or bent back in a pleasing curve. Reflexing adds beauty and grace to the outline of a bow. Reflexed bows may be Long Bows or Flat Bows. There are two methods of reflexing bows. Osage and Yew may be reflexed by means of steam and boiling water. Lemonwood is very difficult to reflex this way. It does not absorb moisture readily and is prone to split and check from the heat. The other way is to glue a reflex in the ends-it is done by laminations. Flat bows are easiest to reflex, and most reflexed bows are of the Semi-Indian Flat Type.

First Method - Assuming that you have a flat osage or yew stave, proceed the same as if you were making a flat bow, but before you cut your notches in the ends, they are reflexed or bent back. A water pail, two wooden forms, and about two dozen rubber strips cut from an old inner tube constitute your bending equipment. Rubber strips should be I ' wide.

The wooden form is made from boards 1312" thick, or two 1" boards nailed together. The shape with measurements is given on Plate 6.

Boil the ends of the limbs, one end at a time, until the wood is soggy, soft and pliable. This takes three to four hours. Bind the ends to the wood forms with the rubber strips. Stretch the rubber well and bind tightly. As you bind, the rubber will pull the ends down along the curved forms. Begin binding at the bottom of the curve and work up (towards the ends of the stave) so the wood is always covered with rubber in order that splinters may not lift. The stave ends should be left in the forms in a dry place, not too hot, for three or four days. All exposed parts of the stave should be shellacked to prevent possible checks from drying. After the rubber binding and forms have been taken off, allow the stave ends to dry out for four or five days to be sure they are perfectly dry and set. Then cut the notches, brace or string the bow as described before, tiller the limbs to a perfect bend, scrape, sandpaper, handle and finish.

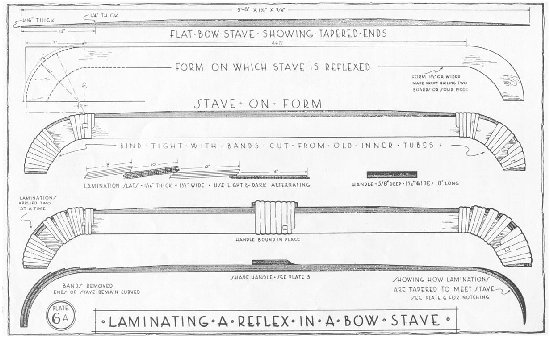

Second Method - This, in the writer's opinion is by far the best way. It results in a reflex of beauty and grace, and is in to stay; the reflexes made by the first method may eventually pull out. Assuming that you are going to reflex a 5'8" Flat Bowstave either of Lemonwood, Yew or Osage, the first step is to flatten the ends of your stave with a long 12" taper. The tips or ends of the stave should be thinned down to 1/16" and increase in thickness to Y4" at the 12" mark. This permits bending the tips around a form as shown on Plate 6-A. Prepare two sets of lamination slats (ten slats in all). These are to be about 1/16" thick. Each set consists of: I piece 14" long, 2 pieces 12" long, I piece 10" long, 1 piece 8". If these slats are of contrasting colors-for instance, lemonwood and black walnut, or lemonwood and rosewood, the finished bow will be very handsome. Prepare a wooden form as shown on Plate 6-A. Place the stave on the form and bind the thinned ends down around the curved extremities of the wooden form. Use strips of rubber Y2" wide cut from an inner tube. Leave the stave overnight so the ends take a set. Prepare good, thick, lumpless, creamy waterproof glue. It is possible to glue on two lamination slats at a time. Apply glue liberally to the 14" piece, place it over the end; apply glue liberally to one of the 12" pieces and bind these down around the form ends with strips of rubber. Be sure the ends are lined up evenly with the tips of your stave. Continue glueing these slats on around the form ends until you have built up about a half inch of laminations in a reflexed or curved form. Let the glue job dry at least a week before shaping the bow. After the laminationg are well set, the step-like ends of the slats are all tapered off as shown on Plate 6-A.

Second Method - This, in the writer's opinion is by far the best way. It results in a reflex of beauty and grace, and is in to stay; the reflexes made by the first method may eventually pull out. Assuming that you are going to reflex a 5'8" Flat Bowstave either of Lemonwood, Yew or Osage, the first step is to flatten the ends of your stave with a long 12" taper. The tips or ends of the stave should be thinned down to 1/16" and increase in thickness to Y4" at the 12" mark. This permits bending the tips around a form as shown on Plate 6-A. Prepare two sets of lamination slats (ten slats in all). These are to be about 1/16" thick. Each set consists of: I piece 14" long, 2 pieces 12" long, I piece 10" long, 1 piece 8". If these slats are of contrasting colors-for instance, lemonwood and black walnut, or lemonwood and rosewood, the finished bow will be very handsome. Prepare a wooden form as shown on Plate 6-A. Place the stave on the form and bind the thinned ends down around the curved extremities of the wooden form. Use strips of rubber Y2" wide cut from an inner tube. Leave the stave overnight so the ends take a set. Prepare good, thick, lumpless, creamy waterproof glue. It is possible to glue on two lamination slats at a time. Apply glue liberally to the 14" piece, place it over the end; apply glue liberally to one of the 12" pieces and bind these down around the form ends with strips of rubber. Be sure the ends are lined up evenly with the tips of your stave. Continue glueing these slats on around the form ends until you have built up about a half inch of laminations in a reflexed or curved form. Let the glue job dry at least a week before shaping the bow. After the laminationg are well set, the step-like ends of the slats are all tapered off as shown on Plate 6-A.

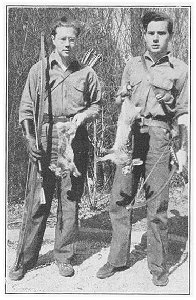

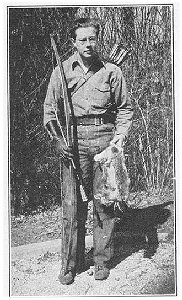

HUNTING BOWS

The typical Hunting Bow is about 5'8" long, Flat, Semi-Flat or Long Bow type. Bois d'arc (osage) is tough and dependable. The bow is plain ended and backed with rawhide. The string is oversized for safety and the handle is of heavy calf-skin or cowhide.

There are no frills on a good hunting bow -sturdiness and dependability are what count. For big game hunting the bow is around 70 lbs., some go as high as 80 lbs.

There are no frills on a good hunting bow -sturdiness and dependability are what count. For big game hunting the bow is around 70 lbs., some go as high as 80 lbs.

Osage Orange is the most dependable wood at these heavy pulls. These bows are intended to drive big, broadheaded arrows with 3/8" shafts swiftly and surely to the mark and are made accordingly.

For hunting small game, any kind of a bow 45 to 55 lbs. pulling weight will do. They may be plain ended, tipped with horn, fibre or metal and be either the long bow or flat bow type. Whether the bow is made of Lemonwood, Osage or Yew is immaterial. The arrow used in these lighter bows is 5 /16" or 11 /32" in diameter, is tipped with a small bunting head, and is fletched with long low triangular feathers.

PREFACE

| Archery |

| Target Shooting |

| Roving |

| Hunting |

| Archery Games |

THE FUNDAMENTALS OF ARCHERY

| Archery Tackle |

| Stringing or Bracing the Bow |

| Shooting the Bow |

MAKING ARCHERY TACKLE AS A HOBBY

| Archery Camp Program |

| Making Bowstrings |

| Bow Woods and Bow Staves |

| Arrow Woods and Arrows |

| How to Take Care of Your Bows and Arrows |

| Common Archery Terms |

| Title Page |

Osage Orange bowstaves, unlike Lemonwood, come directly from the log section, with the bark, heartwood and sapwood intact. Before the staves are stored away for seasoning, the bark is removed and the staves given a coat of shellac. This permits them to dry out slowly and prevents warping and checking.

Osage Orange bowstaves, unlike Lemonwood, come directly from the log section, with the bark, heartwood and sapwood intact. Before the staves are stored away for seasoning, the bark is removed and the staves given a coat of shellac. This permits them to dry out slowly and prevents warping and checking.

Second Method - This, in the writer's opinion is by far the best way. It results in a reflex of beauty and grace, and is in to stay; the reflexes made by the first method may eventually pull out. Assuming that you are going to reflex a 5'8" Flat Bowstave either of Lemonwood, Yew or Osage, the first step is to flatten the ends of your stave with a long 12" taper. The tips or ends of the stave should be thinned down to 1/16" and increase in thickness to Y4" at the 12" mark. This permits bending the tips around a form as shown on Plate 6-A. Prepare two sets of lamination slats (ten slats in all). These are to be about 1/16" thick. Each set consists of: I piece 14" long, 2 pieces 12" long, I piece 10" long, 1 piece 8". If these slats are of contrasting colors-for instance, lemonwood and black walnut, or lemonwood and rosewood, the finished bow will be very handsome. Prepare a wooden form as shown on Plate 6-A. Place the stave on the form and bind the thinned ends down around the curved extremities of the wooden form. Use strips of rubber Y2" wide cut from an inner tube. Leave the stave overnight so the ends take a set. Prepare good, thick, lumpless, creamy waterproof glue. It is possible to glue on two lamination slats at a time. Apply glue liberally to the 14" piece, place it over the end; apply glue liberally to one of the 12" pieces and bind these down around the form ends with strips of rubber. Be sure the ends are lined up evenly with the tips of your stave. Continue glueing these slats on around the form ends until you have built up about a half inch of laminations in a reflexed or curved form. Let the glue job dry at least a week before shaping the bow. After the laminationg are well set, the step-like ends of the slats are all tapered off as shown on Plate 6-A.

Second Method - This, in the writer's opinion is by far the best way. It results in a reflex of beauty and grace, and is in to stay; the reflexes made by the first method may eventually pull out. Assuming that you are going to reflex a 5'8" Flat Bowstave either of Lemonwood, Yew or Osage, the first step is to flatten the ends of your stave with a long 12" taper. The tips or ends of the stave should be thinned down to 1/16" and increase in thickness to Y4" at the 12" mark. This permits bending the tips around a form as shown on Plate 6-A. Prepare two sets of lamination slats (ten slats in all). These are to be about 1/16" thick. Each set consists of: I piece 14" long, 2 pieces 12" long, I piece 10" long, 1 piece 8". If these slats are of contrasting colors-for instance, lemonwood and black walnut, or lemonwood and rosewood, the finished bow will be very handsome. Prepare a wooden form as shown on Plate 6-A. Place the stave on the form and bind the thinned ends down around the curved extremities of the wooden form. Use strips of rubber Y2" wide cut from an inner tube. Leave the stave overnight so the ends take a set. Prepare good, thick, lumpless, creamy waterproof glue. It is possible to glue on two lamination slats at a time. Apply glue liberally to the 14" piece, place it over the end; apply glue liberally to one of the 12" pieces and bind these down around the form ends with strips of rubber. Be sure the ends are lined up evenly with the tips of your stave. Continue glueing these slats on around the form ends until you have built up about a half inch of laminations in a reflexed or curved form. Let the glue job dry at least a week before shaping the bow. After the laminationg are well set, the step-like ends of the slats are all tapered off as shown on Plate 6-A.

There are no frills on a good hunting bow -sturdiness and dependability are what count. For big game hunting the bow is around 70 lbs., some go as high as 80 lbs.

There are no frills on a good hunting bow -sturdiness and dependability are what count. For big game hunting the bow is around 70 lbs., some go as high as 80 lbs.